Generative Technology for Teacher Candidates: The Assignment

Dana L. Grisham

My friend and colleague, Linda Smetana, and I have been working together since about 2004. She’s a full professor at CSU East Bay (Hayward, CA), from which I retired in 2010. Linda is one of those extraordinary scholars and teacher educators who stays close to her field—she teaches one day per week in a Resource classroom in the West Contra Costa Unified School District—and also works full time at the university, where she specializes in literacy teacher education in both special and general education. Recently, Linda and I have been investigating the intersections of literacy and technology in teacher preparation together and I’d like to share with you a project we just completed and the results of which are going to be published in a book edited by Rich Ferdig and Kristine Pytash, due out later in 2013.

Our belief is that “generative” technology needs to be infused into teacher preparation. Technology in teacher preparation tends to be “silo-ed” in the programs where we teach. Currently, candidates at our university have one technology course, based on the ISTE standards, but bearing relatively little on pedagogy for teaching. By generative technology, we mean that the technology is embedded in the content of the course in teaching methods, rather than something “added on.”

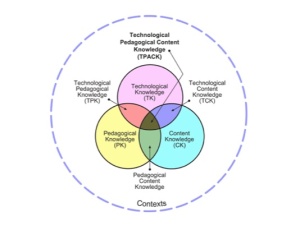

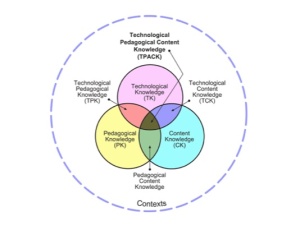

The basic framework that we used for the assignment was the TPACK model (Mishra & Koehler, 2006) that has appeared in this blog before:

The TPACK model asks the teacher to look at the content of the lesson, or what we want students to learn, as well as the pedagogy (how best to teach this content), and then at the technological knowledge that might be advanced in the lesson. Where the three elements intersect is known as TPACK or the theoretical foundation and link between technology and praxis. In our courses, we have presented TPACK as the goal for integrating meaningful technology into lesson planning and teaching.

The participants in our recent study consisted of 21 teacher candidates in the fifth quarter of a seven-quarter post-baccalaureate teacher preparation program; 17 of these candidates were simultaneously completing their masters degree in education while 18 of the 21 participants were earning their education specialist and multiple subject (elementary) credentials.

In creating the assignment, we carefully considered the context for teaching of the candidates in the course, structuring the assignment so that all candidates could successfully complete it. Candidates had different levels of access to student populations. Accessibility ranged from 30 minutes a day three days a week, to the full instructional day five days a week. Teacher candidates also taught different subjects among them: English, History, Writing, Reading, Language Arts, Study Skills, and Social Skills. To insure that teacher candidates considered all aspects of their assignment in their write-ups of the project, Linda provided guidelines for the reflection. Students were responsible for learning to use the tools they chose. Linda collected and we jointly analyzed the data. Findings from the research were uniformly positive. In fact, right now Linda is doing post-research interviews with a couple of the candidates who have really taken to the integration of technology into their teaching.

For the purposes of this post, I would like to share the assignment with you. In my next post I plan to share a couple of the projects. Teacher candidates were provided with guidelines for the technology assignment and provided with a list of potential tools that they might use for the assignment. They learned the TPACK model for planning. Below is the technology assignment from Linda’s syllabus and the list of technology tools (free or very inexpensive) provided for students to investigate. We offer this with complete permission for other teacher educators to use or modify for use in their courses.

The Generative Technology Assignment

The Common Core Standards mandate the use of technology for instruction, student work, and student response. Students with special needs, especially those with mild moderate disabilities may not have access to technology or their access may be limited to hardware and software that may not be useful to support the learning process.

During the second month of the class, we will have three independent learning sessions. These sessions are intended to enable you to complete the technology assignment. This assignment focuses on integrating technology with academic skill development, core content with teacher and student creativity. The focus should be on an aspect of literacy or multiple literacies.

In this assignment you will use technology to develop a set of learning sequences for use with your students. You may complete this assignment in groups of no more than two individuals one of the technology tools in the syllabus or one that you locate on your own. If completed in pairs, the finished product must demonstrate increased complexity and include the work of students in both individuals’ classrooms.

Your technology assignment should enhance the learning of your students. Prepare an introduction to the presentation to educate your viewer. Think about the content of the presentation, reason for the your selection this medium and/or process. Share how your presentation meets the needs of your students and reflects their knowledge. The assignment must incorporate student work. Identify how the students participated in the development and creation of the assignment.

Prepare a thoughtful reflection of your thoughts on the process and the final product including the preparation, implementation and evaluation of the product and the management of students and content. This reflection should be descriptive and include specific examples. It may be submitted as a word document.

Place your project on a flash drive that may be placed into the classroom computer for projection. Use your student work of materials from the web, interviews, u-tube and anything else that will capture students’ attention.

Technology Web Resources Provided to Teacher Candidates

VoiceThread http://www.voicethread.com.

Animoto http://www.animoto.com/education

ComicCreator http://www.readwritethink.org/files/resources/interactives/comic/index.html

Edmodo http://www.edmodo.com

Glogster http://www.glogster.com

Prezi http://www.prezi.com

Popplet http://popplet.com

Slidepoint http://www.slidepoint.net

Storybird http://storybird.com

Strip Designer http://itunes.apple.com/gb/app/strip-designer/id314780738?mt=8

(iPad app)

Stripcreator http://stripcreator.com

Screencast http://screencast.com

Screencast-o-matic http://screencast-o-matic.com

Cool Tools for Schools http://wwwcooltoolsforschools.wikispaces.com/Presentations+Tools

Toontastic http://launchpadtoys.com/toontastic/

In addition to the assignment, teacher candidates were provided with guidelines for reflection, seen below.

Questions to Guide Reflection

What and how did students learn? Include both intentional and unintentional lessons.

What did you learn?

What would you do differently if you were to do this project again?

What were the greatest successes of this project?

How would you improve this project?

What advice would you give a teacher contemplating a similar project?

What kinds of questions did students ask?

Where were students most often confused?

How did you address the needs of different learners in this project?

What resources were most helpful as you planned and implemented this project?

To scaffold teacher candidates application of technology to lesson planning for the project, each one provided Linda with a proposal to which she gave feedback. Each proposal contained the following components: Context, Students, Standards (literacy and NETS•S standards), Technology, Process, and Product.

Every student completed the assignment successfully and their reflections are highly interesting….more to come! In my next post, I will share with you some of the amazing projects that Linda’s teacher candidates produced.

References

Grisham, D. L. & Smetana, L. (in press). Multimodal composition for teacher candidates: Models for K-12 writing instruction. In R. Ferdig & K. Pytash (Eds.). Exploring Multimodal Composition and Digital Writing. Hershey, PA: I-G-I Global.

Mishra, P. & Koehler, M. J. (2006). Technologiical Pedagogical Centent Knowledge: A new framework for teacher knowledge. Teachers College Record, 108, 6, 1017-1054.

Filed under: collaboration, differentiation, digital content creation, digital tools, media literacy, multimodal, new literacies, teacher education, Uncategorized, Web 2.0, writing | Tagged: Common Core, Grisham, instructional strategies, multiliteracies, teacher preparation, Web 2.0 | 1 Comment »