A guest post by Nance S. Wilson, State University of New York at Cortland

This post describes how teachers can engage students in interactive, asynchronous on-line discussions. These discussions not only play an important role in online and hybrid classes; but are critical to assuring active participation by students. On-line discussions can also enhance students’ academic performance (Althaus, 1997), and promote higher-order thinking and critical thinking skills when discussion activities are properly designed (Larkin-Hein, 2001).

However, assuring that asynchronous discussions are truly interactive is a difficult proposition as students are often concerned with their grades and completing their assignments. Sun and Gao (2016) identified issues with the traditional threaded discussion forums because “the chronological and hierarchical structure fails to show the interrelationships of postings or the importance of threads, which may prevent effective discussions from happening” (p. 73).

Therefore, the instructor must use a variety of tools to design the discussion in a manner that compels students to interact with each other (Maddox, 2012; Wood & Bliss, 2016).

My research has revealed two important tools for this structuring in an online course. The first tool is the design of the discussion itself. The second is the application utilized to facilitate the discussion. This is true whether the asynchronous discussion occurs in a hybrid or completely on-line setting. The lessons reported in this post are from an on-line disciplinary literacy class with graduate and undergraduate students.

Interactive, asynchronous discussions should be designed around giving students multiple opportunities to collaborate around a single text and/or topic. In my study of the on-line literacy class, students were asked to complete a series of activities around a textbook (Kane, 2011). For instance, when reading Chapter 3, students were given the following directions:

This is a collaborative reading activity. That means that you will work with your collaborative reading group in OneNote. You will also keep personal notes in your Collaborative Reading Personal Notes Journal.

Go to Chapter 3 of the Kane textbook.

Skim the chapter.

Create three of your own questions to guide your reading of the chapter. (Note: In an earlier module students were introduced to Bloom’s Taxonomy and what makes a good question.)

Using OneNote, visit the Collaborative Reading Group. Share all of your questions with your small group by midnight September 29th. You should also share the following with your group:

- Think about how you interact with your textbooks. Do you always read assignments? Why, or why not?

- Do your teachers actually show you how best to read and use your textbooks?

- Is it necessary to read the textbooks in order to do well in the classes?

- Do your teachers know when a significant percentage of students don’t read the assigned material? If so, what is their reaction? Do they do anything about it, or try to find out why the text wasn’t read? Are there consequences?

- What will you do if your students don’t read the textbook assignments you give? (Kane, 2011, p. 58)

Note/Mark the questions in the group collaboration space that you believe will help you comprehend the chapter and tell your group mates why. This happens asynchronously.

The discussion leader will use what you say about the questions to determine 3 to 5 questions you will answer beyond the guiding questions presented below. This needs to be completed by midnight September 30th.

Read the chapter individually. As you read, find the answers to your questions, answer the question below, and take notes in your Collaborative Reading Personal Notes Journal create a new journal entry and make sure that you include your responses to the questions from your group citing specific information from the reading and looking for ideas to use in your future classroom as well as personal notes to help develop your understanding of the chapter.

Also, answer the following question:

Imagine that you are being interviewed for a teaching job in your content area. The search committee, consisting of a principal, a curriculum coordinator, and several teachers, informs you that the school you hope to work in has a policy of using no textbooks! They ask you to surmise what the philosophy underlying this decision might be and ask you what kinds of materials you would use and how you would teach under these circumstances. Write in your Journal, thinking through how you might envision your job and answer your interviewers (Kane, 2011, p. 85).

After reading go back to your group collaboration page (OneNote) for the readings and share three things with your group:

- any problems you had with any of the questions

- a response to one question created by your group (not previously answered in the collaboration section by a member of your group)

- something from the reading that you can use in your future classroom or that you wish you had in school or that made you think about reading in your discipline.

After sharing with your group, respond to at least one group member regarding their after-reading posts.

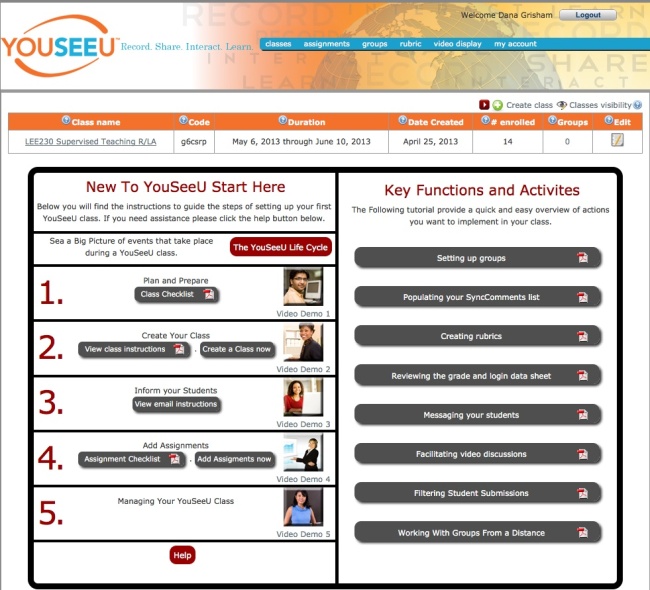

Notice that the directions encourage students to engage in multiple discussion opportunities with their peers. The first begins around a pre-reading of the chapter. During reading, the students are working independently in a traditional BlackBoard journal (see figure 1).

Figure 1: Excerpt from a BlackBoard Journal

After reading, students return to their group to share their thoughts and talk asynchronously. The back and forth of the actual assignment around the reading models both the interactive reading process and requires that students share with one another their reading process. It is important that students share their thinking processes because this helps to develop their metacognitive thinking about the content as well as the reading process (Paris & Winograd, 1990, Garrison, 2003; Akyol, & Garrison, 2011). Thus, the design of the discussion facilitates the students as they engage in interactive conversations and helps to build thinking and learning in an on-line environment (Wood & Bliss, 2016).

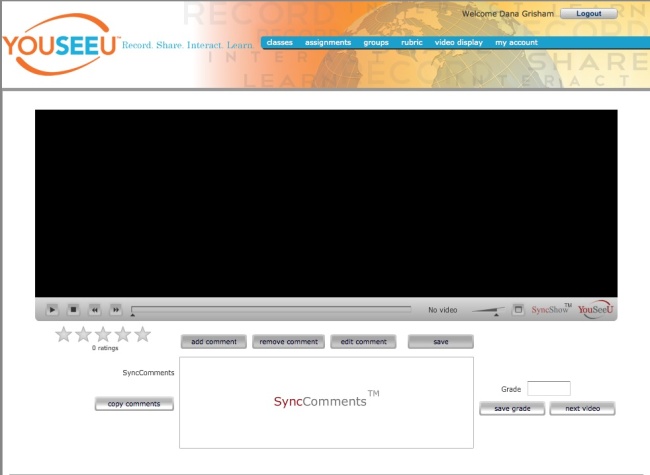

The second tool, Microsoft OneNote, was chosen because it offers students opportunities to move beyond the vertical written asynchronous discussion. In order to facilitate the discussion, the instructor divides the students into small groups and then sets up a notebook for each small group of students. In OneNote student notebooks, there can be pages and subpages to differentiate between sections. For instance, each module can have a page. Then within the module page students can set up sub-pages for before, during and after reading tasks to be completed with the group. On each page, students post into text boxes. They can place their text boxes vertically and horizontally (See Figures 2 & 3). Students can also insert audio comments (See Figure 3).

Figure 2: Overview of a OneNote Notebook

Figure 3: Close up of OneNote Conversation

Thus, using OneNote as a tool changes the nature of the discussion from “prompt to response” to “prompt to response to response:” to “student created questions to response to a student to student conversation.” By changing the format of the conversation from a purely print-based vertical format students are able to have asynchronous conversations on-line that more closely mirror a live discussion. The discussion can be viewed with or without viewing the names of the participants. The figure above is an example of how OneNote works with students’ creation of questions.

The figures are an overview of an extended conversation. Figure 1 demonstrates students posting their initial pre-reading questions on the left while different group members discuss the questions to the right. As the respond to each other’s posts, they indent or move their statements or questions further to the right. The bottom left of figure 1 is a synthesis of the discussion by the discussion leader.

Figure 2 is also a look into a pre-reading discussion around questions. You will notice how students identify questions that they like to the right of the questions posted. Please will also notice that there are two audio posts. The audio posts have student’s thoughts on the questions. The content is similar to the post the written responses. In both figures, you will notice that as students work to finalize their questions for reading they are discussing why they believe different questions will support them during reading with each student going back and forth at least two times before the leader uses the thoughts to develop final questions.

The figures of the discussions are just a glimpse of how careful design of both the discussion opportunity and the thoughtful selection of the tool can create a non-linear asynchronous discussion that supports students to develop a careful reading of the assigned text while engaging in a discussion that is interactive and multimodal.

Microsoft OneNote offers a way to build student engagement and involvement without some of the pitfalls of traditional on-line discussions threads. Since the discussions are not limited by chronological and/or hierarchical structure, students are able to think through their responses while providing a structure that promotes connecting ideas thus avoiding one of the negative issues of threaded discussions, inefficiency in promoting interactive dialogues due to structure (Thomas, 2002). The move away from traditional threaded discussions allows students to post in a structure that follows more of a natural progression, such as one that would occur in a face-to-face class.

References

Akyol, Z., & Garrison, D. R. (2011). Assessing metacognition in an online community of inquiry. The Internet and Higher Education, 14(3), 183-190.

Althaus, S. L. (1997). Computer-mediated communication in the university classroom: An experiment with online discussions. Communication Education, 46, 158–174.

Garrison, D. R. (2003). Cognitive presence for effective asynchronous online learning: The role of reflective inquiry, self-direction and metacognition. Elements of quality online education: Practice and direction, 4, 47-58.

Kane, S. (2011). Literacy & Learning in the Content Areas, 3rd Ed. Scottsdale, AZ: Holcomb Hathaway.

Larkin-Hein, T. (2001). On-line discussions: A key to enhancing student motivation and understanding? 31st ASEE/IEEE Frontiers in Education Conference, Reno, NV. http://fie.engrng.pitt.edu/fie2001/papers/1121.pdf.

Maddix, M. (2012). Generating and facilitating effective online learning through discussion. Christian Education Journal 9(2), 372-385.

Paris, S. G., & Winograd, P. (1990). How metacognition can promote academic learning and instruction. Dimensions of thinking and cognitive instruction, 1, 15-51.

Sun, Y. & Gao, F. (2016) Comparing the use of a social annotation tool and a threaded discussion forum to support online discussions. Internet and Higher Education, 32, 72–79.

Thomas, M. J. W. (2002). Learning within incoherent structures: The space of online discussion forums. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 18, 351–366.

Wood, K. & Bliss, K. (2016). Facilitating successful online discussions. The Journal of Effective Teaching, 16, (2), 76-92.

About the Blogger:

Nance Wilson

Nance S. Wilson, Ph.D., is Associate Professor, Chair of the Literacy Department, and Coordinator of Jewish Studies at SUNY Cortland. She can be reached at nance.wilson@cortland.edu

Filed under: discussion, teacher education | Tagged: digital tools, multimodal, Wilson | 1 Comment »