by Dana L. Grisham (with Thomas DeVere Wolsey and Linda Smetana)

The Need for Vocabulary Learning

The need for breadth and depth of vocabulary accelerates through the grades as students encounter more challenging academic texts in print and on the Internet (CCSS, 2010). Improving students’ vocabulary is critical if students are to develop advanced literacy levels required for success in school and beyond, in the world of higher education and the workplace (Biancarosa & Snow, 2006; Graves & Watts-Taffy, 2008; Lubliner & Grisham, 2012).

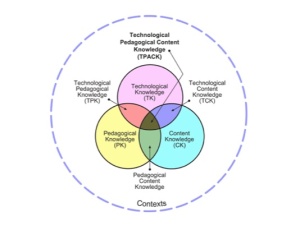

Research suggests that students with a well-developed vocabulary learn many more words indirectly through reading than from instruction (Cunningham & Stanovich, 2001). If wide reading promotes vocabulary development, then conversations about their reading with adults and peers also strengthen students’ word learning (Biemiller & Boote, 2006). The goal of effective vocabulary instruction is to promote a lively interest in words through student expression and participation in a learning community that enjoys playing with words, builds on individual interests as well as curriculum needs, and emphasizes self-efficacy in word learning (Beck, McKeown, & Kucan, 2008; Graves & Watts-Taffy, 2008). As we have noted in this blog, the impact of technology on vocabulary development also needs to be considered (Castek, Dalton & Grisham, 2012). In other contexts, we have suggested that technology integration should be generative in the sense that learners should use technological tools to satisfy their curiosity and to generate creations for learning and for the demonstration of learning (Grisham & Smetana, 2011).

Vocabulary instruction may occur before reading (preteaching important vocabulary), during reading (teaching what emerges as needed), and after reading. Vocabulary Self-collection Strategy or VSS (Haggard, 1982), is an after reading strategy.

The Common Core (2010) requires that technology be integrated into instructional and independent learning sequences. Research has shown that the use of technology and technology-based instruction enhances student learning. In the post-reading vocabulary assignment we explore here, teachers may use use several forms of technology to increase student interest in vocabulary and a variant of the VSS strategy to engage students in more robust vocabulary learning.

Vocabulary Self-collection Strategy Plus (VSS+) occurs after a selection has been read and is based on the principles of VSS (Haggard, 1982), a researched-based strategy that captures the essence of vocabulary learning: multiple exposures to a word, multiple readings of a text, collaboration of students and teacher, oral discussions and presentations, selecting words that are important to know, writing a script and recording a podcast, Internet search for illustrations, and building semantic webs. Recently, two colleagues (Thomas DeVere Wolsey and Linda Smetana) and I worked in a fourth-grade classroom in a public school in Northern California, to teach the students how to make an online dictionary (e-dictionary) page using the VSS+ strategy. The three of us spent three hours with Mr. D’s 33 students, first in the classroom, then in the computer lab at their school.

VSS+ is a structure that becomes familiar to students so they can use it with more independence over time. It takes more time in the beginning as teachers and students get used to the technology, the time, and the process. To teach VSS+ we wanted to use text with interesting or unknown words or text dense with academic language. Mr. D provided us with a passage from the Science textbook in use in his classroom. Mr. D pre-taught some of the vocabulary and students had already read and discussed the package when we arrived.

Collaboration and peer learning are essential to the VSS+ strategy. Mr. D had the students divided into cooperative groups of 4 students. In order to differentiate instruction to meet the learning needs of students, they may be grouped heterogeneously or homogeneously as needed. Mr. D’s students were grouped heterogeneously.

To teach the VSS+ strategy, we began in the classroom with a PowerPoint slide and a demonstration of the strategy. Using a think aloud protocol, I modeled the strategy by presenting a nominated word to the class, and provided suggested answers to the following questions. In the demonstration, we used an example that we constructed on “continent” (see below). These are the three elements that students must consider as they nominate a word.

a. Where is the word found in the text? (Page number; read the sentence aloud)

b. What do the team members think the word means?

c. Why did the team think the class should learn the word? The team must tell the class why the word is important enough to single out for emphasis (a rationale).

During the team presentations of nominated words, we facilitated discussion, listened to students’ projected meanings of the word, and invited class members to contribute additional clarifications of the words. A chosen target word was allocated to each team to prepare an e-dictionary page.

Then came the fun part! We adjourned to the computer lab where we asked students in Mr. D’s class to use two formats for their e-dictionary pages: PowerPoint (like our example below) and a program called Thinglink.

In the lab, under teacher supervision, team members used the Internet to locate images and or definitions for the target word and then collaboratively determined which of the images/definitions best fit their prediction of the word meaning.

We proposed the following formatting for the eDictionary:

Word and Written Definition

Image selection from the Internet, Photos, Illustrations or Student Drawings (if a scanner is available)

Semantic web (we used WordSift)

Student audio recording about the word (critical thinking about own word learning)

Arrangement of the PowerPoint or Website page

Audio recording by students of the main elements of the word exploration

Posting to website (classroom e-Dictionary)

In the following example, the three of us used PowerPoint to make a sample e-dictionary page using the word “continent.” In the PowerPoint page is an audio recording that cannot be loaded into WordPress. To hear this recording, please visit

http://media60.podbean.com/pb/5d2ff0db75b8e90568ffd2295b4362b8/52693971/data1/blogs25/353339/uploads/ThinglinkContinents.mp3

Next week in Literacy Beat, Linda, DeVere and I will talk more about the work we did with Mr. D’s students and share examples of their PowerPoint and Thinglink pages with you.

References

Biancarosa, C., & Snow, C. E. (2006). Reading next—A vision for action and research in middle and high school literacy: A report to Carnegie Corporation of New York (2nd ed.). Washington, DC: Alliance for Excellent Education.

Biemiller, A. & Boote, C. (2006). An effective method for building meaning vocabulary in primary grades. Journal of Educational Psychology, 98, 44-62.

Blachowicz, C. L. Z., & Fisher, P. (2000). Vocabulary instruction. In R. Barr, P.

Mosenthal, P. S. Pearson, & M. Kamil (Eds.), Handbook of Reading Research, vol. III, (pp. 503-523). White Plains: Longman.

Castek, J., Dalton, B. & Grisham, D. L. (2012). Using Multimedia to Support Generative Vocabulary Learning. In J. F. Baumann & E. J. Kame’enui (Eds.). Vocabulary Instruction: Research to Practice (2nd Edition). New York: Guilford.

Common Core State Standards Initiative. (2010). Common Core State Standards for English Language Arts & Literacy in History/Social Studies, Science, and Technical Subjects. Washington, DC: CCSSO & National Governors Association.

Cunningham, A.E. & Stanovich, K. E. (2001). What reading does for the mind. American Educator, 22, 1/2, 8-15.

Graves, M.E. & Watts-Taffy, S. (2008). For the love of words: Fostering word consciousness in young readers. Reading Teacher, 62, 99.185-193.

Haggard, M. (1982) The vocabulary self collection strategy: An active approach to word learning. Journal of Reading, Vol. 26, No. 3 (Dec., 1982), pp. 203-207.

Grisham, D.L. & Smetana, L. (2011) Generative technology for teacher educators. Journal of Reading Education, 36, 3, 12-18.

Lubliner, S. & Grisham, D. L. (2012). Cognate Strategy Instruction: Providing Powerful Literacy Tools to Spanish-Speaking Students. In J. Fingon & S. Ulanov (Eds.), Learning from Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Classrooms: Promoting Success for All Students (pp. 105-123). New York: Teachers College Press.

1

Filed under: collaboration, collaborative writing, Common Core, digital content creation, Grisham, media literacy, multimodal, new literacies, technology integration, vocabulary, Web 2.0, writing | Tagged: Grisham, vss+, Wolsey | 5 Comments »